Therapeutics (also called modalities) are drugs that are administered to patients to treat diseases and disorders. There are five main classes of therapeutics and modalities: small molecules, large molecules, gene therapy, cell therapy and RNA therapy. Specific examples include antibodies, bispecific antibodies, small molecule drugs, T cells genetically engineered to express CARs, siRNAs, ASOs, etc. All therapeutics have one thing in common: they must be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before they can be marketed and sold in the U.S. to treat patients.

NDAs, BLAs, CDER, and CBER

Therapeutics in the U.S. are approved under either an NDA (New Drug Application) or a BLA (Biologics License Application). See our blog post Approval and Regulation of Therapeutics and Modalities at the FDA, which explains the different centers at the FDA. There are two centers at the FDA responsible for reviewing and approving NDAs and BLAs: the Center for Biologics and Evaluation and Research (CBER) or the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Whether a therapeutic is approved under an NDA or BLA, or by CDER or CBER, depends on the composition of the therapeutic.

The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906

Historically, regulation of drugs and food in the U.S. began with the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. Although meant to safeguard public health, this law did not require government review or approval for new drugs. So, drugs could be sold and marketed without first proving that the drug was safe or effective in humans. Shockingly, under the Pure Food and Drug Act selling toxic drugs was not illegal in the U.S.

The Biologics Act of 1902

At this same time vaccines, serums, and other biologicals were also not regulated by the government. Vaccines and other biological products had been around since the 1700s and the manufacturing methods created a danger of contamination. For example, the diphtheria anti-toxin was produced in horses by injecting them with a small amount of diphtheria to generate the anti-toxins. The serum from these immunized horses was extracted and injected into children. However, the extracted serum was contaminated with tetanus and resulted in the death of children. This caused the government to pass the Biologics Act of 1902. The Biologics Act required biologics to be manufactured in establishments holding a license issued by the federal government, where the government could inspect these facilities. The reasoning behind the requirement of a license was that regulation of the manufacturing process would ensure the safety of the resulting biological product.

Thus, drugs and biological products were treated differently under these two statutes.

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) of 1938 replaces the Pure Food and Drug Act

By the 1930s there was dissatisfaction with the strength of the Pure Food and Drug Act in ensuring that drugs sold in the U.S. were safe and effective. However, it was the sulfanilamide tragedy that caused the government to act quickly and pass new legislation. Sulfanilamide was a drug used to treat certain infections and it was sold and distributed in tablet and powder form. Demand rose for a liquid formulation of the drug and the company selling sulfanilamide tablets began experimenting with a new liquid formulation. Chemists discovered that sulfanilamide would dissolve in diethylene glycol and started manufacturing and distributing this new liquid formulation in 1937. Under the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, safety or toxicity studies were not required before a drug was sold and distributed to U.S. patients. Although diethylene glycol dissolved sulfanilamide, it was a deadly poison. Doctors reported patient deaths and FDA inspectors and chemists set out to recover the batches of the formulation distributed to the public. In total, only approximately 234 gallons of the liquid formulation was recovered from the 240 gallons distributed. The remainder was consumed and caused the deaths of patients, many of them children.

The Sulfanilamide tragedy hastened the enactment of the 1938 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA), which created a new system to regulate and approve drugs to be sold in the U.S. The FDCA had to address how to deal with the drugs already being sold in the U.S. Under section 505 of the FDCA, manufacturers had to submit to the FDA evidence that a “new drug” was safe before it could be sold in the U.S., essentially creating the new drug application, or NDA. A “new drug” was defined as a drug that was not GRAS: generally recognized as safe. Once submitted to the FDA, an NDA would become effective if the government didn’t reject the application within sixty days. There was no requirement to wait for an approval.

Many marketers at this time determined that their drugs were not new, or they were GRAS, or generally recognized as safe. As a result, many drugs were sold in the U.S. without an NDA.

The Public Health Service Act (PHSA) of 1944 incorporates the Biologics Act of 1902

Six years after enacting the FDCA, the U.S. passed the Public Health Service Act (PHSA) in 1944. Within this law, the Biologics Act of 1902 was revised and recodified in section 351 of the PHSA. Section 351 of the PHSA provided that an establishment license could only be issued upon a showing that the establishment and the biological product met standards to ensure the safety, purity, and potency of the product. This new language was interpreted to mean that an establishment license application (ELA) and an approved product license application (PLA) was required for a biological product. The dual licensure requirement was eliminated in 1997 and the government created a single biologics license application (BLA) requirement.

Overlap between the FDCA and the PHSA

Overlap and conflict between the FDCA and the PHSA has been an issue since enactment of the Food and Drugs Act in 1906. This is because the definition of a “drug” under the FDCA is very broad and includes biological products that needed a license under the Biologics Act of 1902. However, the FDA has historically stated that a new drug would not be subject to the FDCA if it was licensed under the Biologics Act of 1902. When the PHSA was enacted, it included a provision stating that nothing in the statue should be construed to modify or supersede the FDCA of 1938. Thus, in the U.S., two different statutes and two different applications regulate the approval of therapeutics: the NDA and the BLA.

This overlap between the FDCA and PHSA has manifested in biological products being approved and regulated under NDAs. Shortly after enactment of the FDCA in 1938, insulin products were approved under NDAs. Human growth hormones derived from the pituitary gland of cadavers was approved in the 1970s under an NDA. Various other hormones or small protein therapeutics were approved under NDAs and not BLAs.

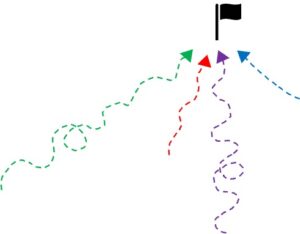

Since the early 1900s the U.S. federal government has treated drugs that are manufactured as tablets and powders (or by chemical synthesis) different from products that are manufactured from animals or cells. This dichotomy still exists today with the NDA and the BLA. The NDA, or New Drug Application came out of FDCA enacted in 1938 and the BLA, or Biologics License Application came out of the PHSA enacted in 1944 (which revised and incorporated the Biologics Act of 1902).

To determine whether a certain modality would be approved under an NDA or BLA, an understanding of the composition of the modality and how the modality is manufactured is required. Science for Bankers offers an Executive Course on Therapeutics and Modalities that covers how each modality is manufactured, along with its composition of matter and its mechanism of action. The course covers the five main classes of therapeutics, and much more. The course is made up of about 45 videos; all under 30 minutes. Watch whenever and wherever. Essentially, a masterclass of therapeutics and modalities, or the science in life sciences.