Our blog post Therapeutics in the U.S.: why are there NDAs and BLAs? covers the history of NDAs and BLAs and why both applications exist in the U.S. for approval of therapeutics. Since the 1900s, the U.S. government has regulated drugs differently. Initially, drugs were regulated under the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, while vaccines, serums, and other biologics made from animals or cells were regulated under the Biologics Act of 1902. The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) of 1938 replaced the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. The Public Health Service Act (PHSA) of 1944 incorporated the Biologics Act of 1902. Thus, since 1944, two major and separate laws regulate therapeutics in the U.S.: the FDCA and PHSA.

FDCA and PHSA

Under the FDCA, a therapeutic is approved under an NDA, or new drug application. Under the PHSA, a therapeutic is approved under a BLA. Generally, the FDCA (via an NDA) regulates non-biologic drugs (small molecules, oligonucleotides, etc.) and the PHSA (via a BLA) regulates biologic drugs (antibodies, fusion proteins, etc.). However, because the term “drug” is defined so broadly in the FDCA, some biologic drugs have been approved under an NDA.

Hatch-Waxman Amendments

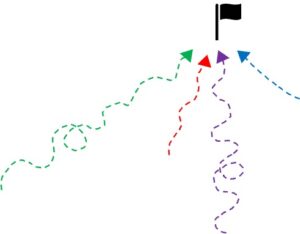

In our blog post Therapeutic approvals: the rise of the ANDA we reviewed how in the 1960s the FDA created two approval pathways for generics, the ANDA and the paper NDA. Then, the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, also known as the Hatch-Waxman Amendments, codified these abbreviated approval pathways into statute. After the Hatch-Waxman Amendments, drugs could be approved under an NDA (via 505(b)(1) of the FDCA), a hybrid NDA (via 505(b)(2) of the FDCA), or an ANDA (via section 505(j) of the FDCA).

But biologic drugs were approved under the PHSA and not the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA). How could a generic biologic drug enter the market?

Harmonizing NDA and BLA approvals

Beginning in the 1990s, efforts were made to harmonize how both classes of drugs, biologics and non-biologics, were approved and regulated by the FDA. For example, interpretation of section 351 of the PHSA required biologic drugs to have an establishment license application (ELA) and an approved product license application (PLA). In 1997 the dual licensure requirement was eliminated and the government created a single biologics license application (BLA) requirement.

In our blog post Approval and Regulation of Therapeutics and Modalities at the FDA, we reviewed the various centers at the FDA. Two centers, CDER (Center for Drug Evaluation and Research) and CBER (Center for Biologics and Evaluation and Research Center for Biologics and Evaluation and Research) are responsible for regulating and approving biologic and non-biologic drugs. In the 1990s, BLAs were reviewed by CBER and NDAs were usually reviewed by CDER. In 2003, the FDA harmonized how NDAs and BLAs were reviewed by consolidating the review of BLAs for therapeutic proteins within the same center that approved NDAs: CDER. Since 2003, CDER has reviewed not only NDAs, but also BLAs for antibodies, fusion proteins, peptides, small proteins, etc.

Pathway for generic BLA

In the 1990s there was debate about whether the FDA could approve a generic of a therapeutic protein under either the FDCA or PHSA. Some legislators argued that the FDA already had authority – via an ANDA or a 505(b)(2) pathway. However, there was controversy. Mainly due to the difference between how NDAs and BLAs are reviewed. This is because at the core of the BLA is the scrutiny on the manufacturing processes, which is not as heavily scrutinized in an NDA. Some argued that the FDA should create a “paper BLA” like the “paper NDA.” Others argued that the FDA had no authority under either statute to create an abbreviated BLA and the FDA would need to wait for Congress to pass legislation.

Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009

Years of debate, hearings, and legislative work culminated in the passing of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCIA). This legislation created the statutory authority for the FDA to approve generic versions of therapeutic proteins, called biosimilars.

There were several key scientific issues that had to be resolved regarding generics of biologic drugs. For example, could another manufacturer duplicate a biologic drug by copying and using the same manufacturing process? Could another manufacturer duplicate a biologic drug by using a different manufacturing process? Are there sufficient analytical techniques to measure protein structure and activity so that the FDA could conclude that a biosimilar is a copy of a therapeutic protein, or a reference product? In regards to safety and efficacy, is it possible to determine that two proteins (i.e., a biosimilar and a reference product) are interchangeable? Ultimately, these scientific questions were resolved and the BPCIA was passed. Under this legislation, an approval pathway for generic biologic drugs was codified in statute. There are many aspects to this law related to patents and regulatory exclusivities, but ultimately, this law gave the FDA the authority to approve biosimilars or generics to biologic drugs.

Five classes of therapeutics and modalities

There are five main classes of therapeutics or modalities: small molecules, protein-based therapeutics, gene therapy, cell therapy, and RNA therapy. Each therapeutic needs to be approved by the FDA, under either an NDA or BLA, before the therapeutic can be marketed and commercialized in the U.S. Because it is so critical for any professional working in life sciences, biotechnology, or pharmaceuticals to understand the five main classes of therapeutics, Science for Bankers created an Executive Course on Therapeutics and Modalities. The course is designed for professional with little to no science background. In approximately 45 videos, each under 30 minutes, a professional can learn the “science” in life sciences.